Introduction: The Intricacies of Karma in Buddhism

The theory of karma stands as one of the most vital, intricate, and challenging concepts within Buddhist philosophy, often leading to misunderstandings. This concept has profoundly shaped Asian civilizations, serving as a cornerstone for the moral codes and religious beliefs of many. Karma is pivotal in Buddhism, acting as a foundation upon which Buddhist teachings are built.

The depths of karma are notoriously difficult to grasp, as its ultimate nature surpasses human comprehension. Analyzing and presenting karma systematically proves exceptionally difficult, which may explain why no single universally satisfying explanation of karma exists in Buddhist literature. This discussion offers a simple introduction to this complex and fundamental Buddhist tenet, based on my personal understanding.

The term “karma” originally signifies action or deed. Yet, in contemporary Buddhism, “karma” encompasses an extremely intricate and multifaceted concept. At its core, karma is defined as the universal law of cause and effect that governs both the natural and moral realms. Although this definition appears straightforward, further examination reveals the intricate and ambiguous nature of karma. For clarity, we will investigate karma from six perspectives.

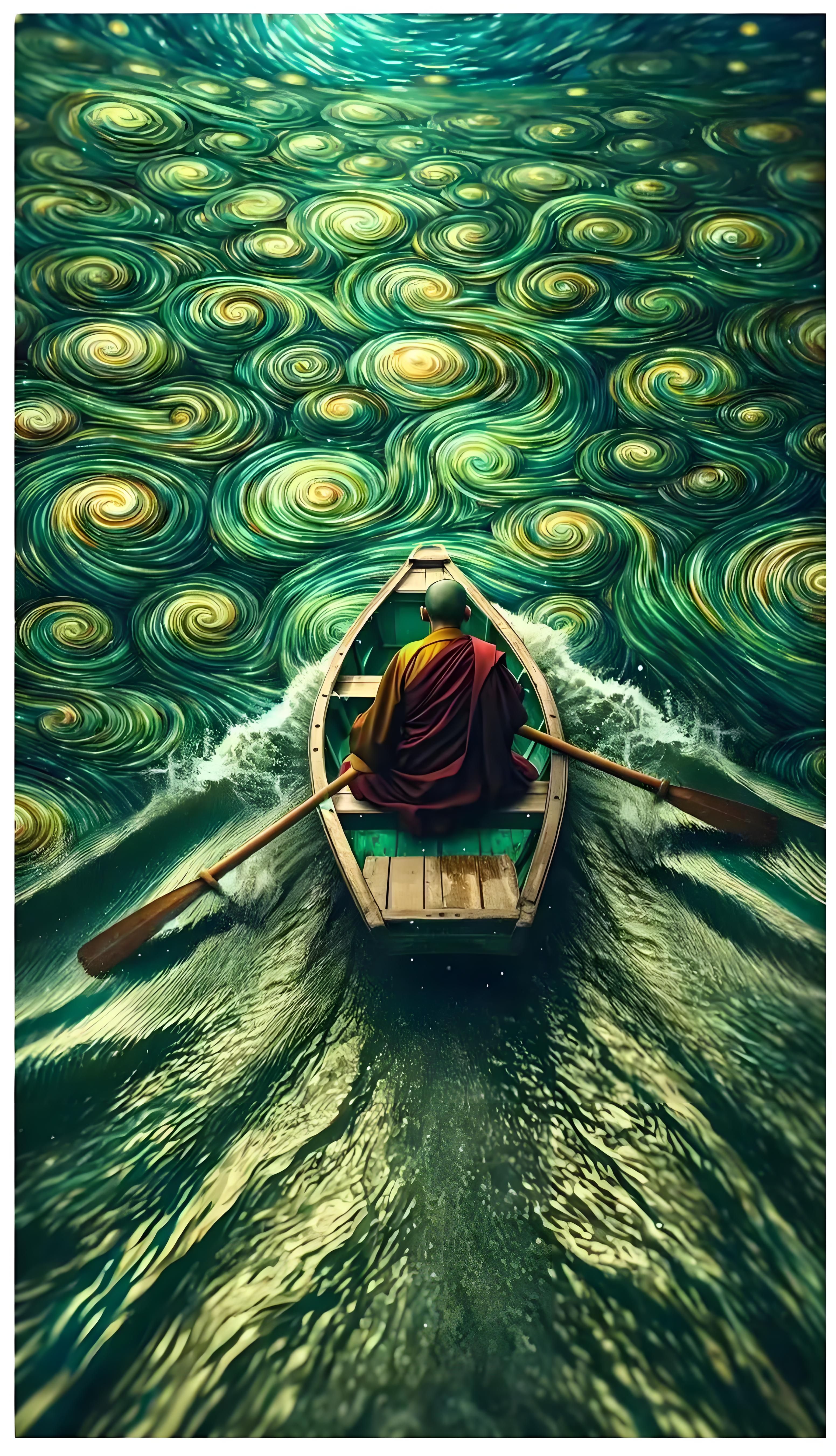

I. Karma as a Force

Every action produces a force, which, in turn, compels us to engage in new actions, and this process creates a continuous cycle, propelling the wheel of karma forward. This force is not always visible, but its effects are certainly felt.

Consider the development of the American West: the construction of roads and railways was essential to opening up the wilderness. Building railways generated new forces, including increased financial resources, labor, and materials. These forces, in turn, led to further activities, creating additional forces.

Similarly, earning money creates the power to purchase and engage in new activities. This can lead to more complex desires and needs, transforming our lifestyles in numerous ways. The original intention of earning money to serve others often shifts into people becoming servants to their money. Likewise, while machines were invented to serve and simplify human lives, they have created more concerns and complexities, making people almost slaves to them.

Therefore, actions not only generate force but also create constraints that compel us to face the consequences of our deeds. “Less is more” is a saying that reflects a desire to avoid getting trapped by the outcomes of certain actions.

The force of karma is usually invisible, yet keenly felt. Observing a busy city street from a high vantage point reveals the chaotic movement of vehicles and people, a force that seems to drive them forward. If we are part of that crowd, we may be less aware of this karmic pull.

Even in an office building, the constant discussions, plans, debates, and schemes being carried out by countless people illustrate an immense force driving them. Each individual’s actions create a specific force; when combined, these forces become a massive collective force, also known as “collective karma.” Individual karma is called “separate karma,” whereas the collective karma is the shared force created by a group. Collective karma influences the course of history, life, and the universe.

In short, karma arises from the fundamental, subconscious desires for survival and activity, fueled by innate desires.

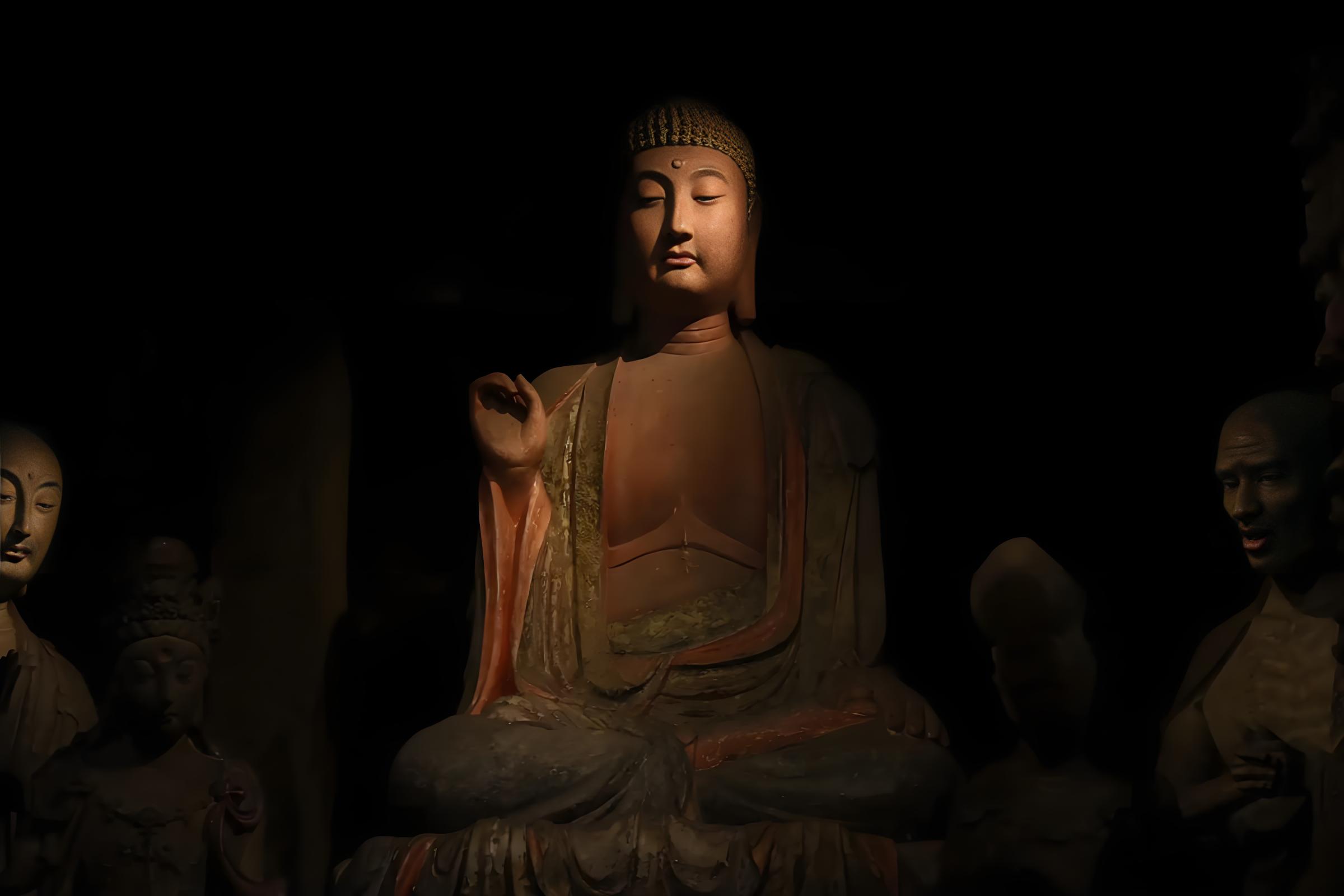

II. Karma as a Mystery

The phenomenon of karma is too profound for human intellect to fully grasp, making it a profound mystery. This mystery is especially apparent in the natural world.

For example, a mother cat has multiple nipples, ensuring that her kittens all have an opportunity to nurse. Consider how problematic it would be if cats or women had only two nipples.

The anatomy of birds, with their light, hollow bones and aerodynamic features, is perfectly suited to flight. The precise design exceeds that of even the most skilled aeronautical engineers. Similarly, the human body is a marvel of intricate systems that work in harmony. The human eye is like a sophisticated camera that possesses capabilities far beyond that of any camera ever created.

It’s true that some high-altitude cameras can capture images more clearly than the human eye, however, this is because their design has been specialized for that particular function. The human eye, though small, has multiple functions such as secreting various types of tears and adjusting its pupil size automatically, focusing, and the ability to express emotion.

The placement of the eyes above the nose is also significant. If they were located below the nose or on the back of the head, vision would be significantly impaired.

The purpose of bodily features, such as eyebrows, highlights the question of the function of human organs. It is thought that the function of the eyebrows is to protect the eyes from sweat. Whether beauty also plays a part, we cannot deny that evolution does include the element of “beauty.”

Furthermore, the products and secretions of animal organs are equally astonishing. Milk, whether from humans, cows, or goats, is rich in essential nutrients. It is the result of the force of karma that mothers produce the ideal nourishment for their offspring, a natural and efficient process. The complementary design of the male and female reproductive systems showcases the power of “natural karma.” The fact that herbivores can survive and thrive on simple grasses also is testament to the mystery of karma.

The world is full of mysteries that we often overlook. A closer observation reveals that everything is marvelous and inexplicable.

Another example can be found in the close relationship between our posture and our psychological state. A gesture such as putting our palms together in front of our chest makes it easier to achieve a state of religious contemplation, while other gestures can hinder that process. This is something that we take for granted; however, when we pause to consider why these things are, we quickly realize that they are too mysterious to comprehend.

Buddhists describe the wonder of life as “the inconceivability of karma,” whereas Christians often attribute this to the wisdom of God. The various mysteries of the universe are all thought to be part of the will of God.

When discussing “divine purpose,” Westerners often use the term “God’s will” to explain situations that defy human understanding. When insurance contracts contain phrases that state the contract is void “under the will of God,” this can be seen as an admission of a reality beyond our human control.

Consider a virtuous couple who have a child who is born blind, deaf, and crippled, suffering from congenital mental disabilities. Westerners may explain this as “God’s will” because their religion struggles to justify the existence of such cruelty. To Buddhists, it is a consequence of negative karma: they would exclaim, “How pitiful! What terrible karmic consequences the baby and the parents are experiencing!” Thus, karma is both a mysterious force and an undeniable destiny, and destiny itself is a mystery, as it cannot be explained by human intelligence.

In the Buddhist text The Questions of King Milinda, the King and the monk Nagasena discuss the mystery of karma: King Milinda questions Nagasena, asking why the fires of hell are said to be many times more intense than earthly fires, and why hell beings are not consumed after so many years in the fire. Nagasena uses the example of animals such as peacocks eating pebbles and sand, that are then digested, to illustrate that while some objects are digestible to some beings, the same objects might not be digestible to another. Likewise, a fetus is not consumed while in the womb. The reason for this, according to Nagasena is the karma of the fetus. Likewise, the beings in hell do not die until their karma has been exhausted.

The mystery of karma cannot always be explained, but we can see it in nature. A peacock can eat poison and become healthy, while a human would likely die from the same poison.

III. Karma as Destiny

Our circumstances vary widely. Some people are born with high intelligence, while others have limitations. Some are attractive, others are not. Some are born with disabilities. These differences are often explained as “fate.” Buddhists explain this by stating that these circumstances are the results of our past karmic actions, and actions in this life determine the next.

We mistakenly believe that we have considerable freedom, but our lives are quite restrictive. A human being does not have the freedom to choose their life. The experience of being born and the reality of death are two events that we are forced into. The power that drives these events is karma.

Karma limits our freedom, forcing us to take on particular lives and fulfill “predetermined” duties. Many of life’s important events are continuations of unfinished tasks from previous lifetimes.

For instance, a person who is frugal and hardworking might amass a fortune. Upon death, they may leave it all to their son, who has never had to work for it. From the perspective of karma, this fortune was something owed to the son from a previous life. The same idea applies to family relationships, often viewed as transactional encounters of debts to be paid and obligations to be fulfilled.

Marriage can also be explained by karma: even if a couple seems perfect for each other, they may end up marrying other people. The most likely explanation for this lies in the unfinished karmic relationships of past lives.

Similarly, individuals born with disabilities are said to have been born with the results of bad actions in their past lives. Geniuses are born with the consequences of good karmic action, because they have already had some level of mastery in their past lives.

When we complete unfinished tasks from previous lives, we generate new karma, perpetuating the cycle of rebirth. So does this mean that karma is a system of predestination? Not exactly, because while karma has constraints, we can choose to engage, or not engage, in certain actions. Therefore, we can choose our karmic consequences to some degree, and through self-improvement, we can transform or purify the nature of our karma.

If karma was entirely a system of predestination, then there would be no use in any religious or moral behavior. The Buddhist concept of karma highlights both the fixed and unfixed elements of human life and existence.

This differs from the Christian idea that human history is part of God’s divine plan. Christians often cite examples of divine intervention, like that of Emperor Constantine, who, after seeing a cross in the sky during a battle, converted to Christianity, which then became the religion of Rome. In contrast, Buddhists view war as the result of collective karma, not divine interference. Thus, Buddhist history is based on natural karma, while Christianity is rooted in divine intent.

Hinduism is a combination of Aryan monotheism and the karmic and yogic beliefs of the indigenous Dravidians. It acknowledges karma alongside divine will and authority. The Bhagavad Gita, an important Hindu scripture, suggests that war is an act of divine will. Through God’s eyes, people who participate in war have already been destined to die, and the war is merely a dramatization. Buddhist perspectives do not agree with this.

In short, karma is an invisible force that shapes our destiny and is a mixture of different types of fixed and unfixed forces.

IV. Karma as a Relationship

Karma is best understood through a series of seven concentric circles, where each circle represents a distinct karmic realm. The largest circle is the realm of universal collective karma, with each subsequent circle decreasing in size, leading to individual karma, or the pure self. Here is a summary of the seven circles:

- Universal Collective Karma

- General Collective Karma

- National Collective Karma

- Specific Collective Karma

- Individual Karma

- Extremely Individual Karma

- Purely Individual Karma

The outermost circle, Universal Collective Karma, applies to all living things, as it pertains to the essential elements required for life, such as sunlight, air, and water. This shared karma creates a very strong constraint, which is difficult to change.

The second circle, General Collective Karma, is shared by all of humanity, and pertains to the ability to use symbols and language, the capacity for moral consciousness, and self-awareness. These traits both enrich and create difficulties in human life. These commonalities are unique to humans and not shared by other living creatures.

The third circle, National Collective Karma, acknowledges that national identity impacts the lives of people. Factors such as international politics and conflict are influenced by the idea of nations, and citizens of a country must adhere to the obligations of their citizenship. This can include military service and taxes. This collective karma places constraints on people which are not always of their choosing.

The fourth circle, Specific Collective Karma, is found in smaller groups, such as school affiliations. The quality of an education, or the professors who teach at a particular institution, are all part of the karma that is shared by a particular group. The members of a school, drama troupe, or political movement all share a similar specific collective karma.

The fifth circle, Individual Karma, is found in families. The family dynamic and the life circumstances of each family vary, but each member is affected by the collective karma of the family. Family members are often tied together by karmic bonds of obligation and duty.

The sixth circle, Extremely Individual Karma, is the karma found in marital relationships or with other close friends and relations.

The seventh circle, Purely Individual Karma, pertains to one’s inner self, the pure ego. Our innermost thoughts, feelings, and desires are only known to ourselves, and are therefore separate from others.

The seven circles explain what is meant by collective and individual karma. Every individual exists within a variety of these circles. This creates an interlinked web, with multiple overlapping levels. Each person is a part of this web, taking on multiple roles at once. At the center, an individual is an ego. Moving outward, they are also family members, citizens, and members of the greater world.

We are all interwoven into a vast karmic web, made up of an infinite number of individuals and connections, and the vast web creates a cycle that is difficult to fully grasp.

Each karmic circle has different levels of malleability. It is much easier to change personal karmic patterns, than it is to change patterns within larger groups. While it is possible to transform our own habits, changing the habits and nature of other people is exponentially more difficult. It is even harder to change that of a collective. Throughout history, people like Buddha have been able to transform themselves and influence the karma of their families, nations, and even all living things. However, the more widespread the group is, the more difficult the change will be.

From this, we can confirm that the transformation of karma has varying degrees of difficulty. The differing degrees of difficulty imply that there is a will to change the environment (or karma), with varying levels of success. This means that the will to transform the environment exists, otherwise, such varying levels of difficulty would not exist. Therefore, the idea that the will can transform the environment is the same as admitting the existence of free will.

The Buddhist sutras often state that the depths of karma are only known to the Buddha, and what is fixed and unfixed is only known by enlightened beings. There is no clear system for distinguishing between fixed and unfixed karma, other than to state that the karma of large groups is typically fixed.

The issue of free will and the necessity of cause and effect has been examined at length by Western philosophers. But this is often overlooked within Buddhist philosophy, which is quite surprising, given its importance to the core tenants of the religion.

When I lecture on karma, listeners often bring up the question of free will. Buddhism does confirm that free will exists, but does not offer philosophical support for this claim. The idea that different levels of karma are easier to transform has been used as support for the idea of free will. This is just an initial attempt to examine this, and further efforts are required.

There are two more reasons why free will must be accepted. First, the existence of free will is an immediate and undeniable reality. The ability to think and critique everything without limitations confirms the existence of free will. Our ability to think is a clear, immediate, and undeniable truth. Second, free will is essential to religious and moral conduct. Without free choice, there could be no concept of good or evil, and religious acts would be impossible. Without free will, we would be complex machines, merely reacting to stimuli.

Therefore, from a practical perspective, we are compelled to accept that free will exists, if morality and religion are to remain.

V. Karma as a Moral Law

Perhaps the most important aspect of karma, from a practical and religious perspective, is that it represents a moral law. The “Principle of Correspondence” is the core idea, which can be summarized as “like causes produce like effects.”

This means that the consequences of an action are similar to the action itself. In nature, this is represented by “you reap what you sow,” or “planting melons will produce melons, and planting beans will produce beans”. The same is true in morality: good actions result in good consequences, and bad actions result in bad consequences.

The Buddhist worldview strongly believes in the principle of correspondence. The Buddha clarifies this in the Srimala Sutra:

The Buddha said, “If a woman was quick to anger and greedy in a past life, she will be born ugly and poor in this life. If she was quick to anger, but also generous, then she will be born ugly, but wealthy. If she had a calm nature but was not generous, she will be born beautiful, but poor. If she had a calm nature and was generous, she will be born beautiful and rich”.

These passages clearly illustrate the principle of correspondence. Beauty, ugliness, wealth, and poverty are all explained with specific causes. It also correlates to The Ten Examples Sutra, which says:

“The patient are born beautiful, while the greedy are born poor. The respectful are born with high status, while the proud are born lowly. Those who slander are born mute, while the skeptical are born deaf and blind. The compassionate live long, while those who kill live short lives. Those who break the precepts are born deformed, while those who follow the precepts are born with perfect senses.”

If there is no corresponding karmic effect, Buddhists believe that either the timing is not right, or the correct conditions have not been met. A seed will not produce fruit on a table, but will require the right environment to grow. So, actions require the correct timing and conditions to manifest results.

In the end, whether divine plan or natural karma is more reasonable is still a matter of debate.

VI. Traditional Views on Karma

(1) Traditional Buddhism believes that “one cause produces multiple effects.” For example, a person who commits murder under the influence of alcohol faces multiple consequences, including remorse, legal repercussions, ruined careers and relationships, etc. There are also future implications in which the murderer will be forced to endure retribution.

Modern people might view these ideas as exaggerated. For example, in one sutra, it is said that a person who threw rice at the Buddha was then born as a great king. In other scriptures, doing bad is said to bring infinite suffering.

Modern readers may see these as parables designed to encourage people to be moral, instead of a reflection of reality.

There is a Tibetan folktale about an elderly woman who attended a dharma talk on karma. After the talk, the woman told the lama that, according to the scriptures, the good karma would make even her a buddha, and the bad karma would send both her and the lama to hell. This shows that regular people are capable of having profound realizations.

While this shows that people have natural empathy, it is important not to dismiss the idea of cause and effect. In karma, the effects are almost always greater than the initial cause. As with the example of the murderer, there are multiple results for a single action. The sutras have a philosophical basis for this, as we will discuss.

From a religious viewpoint, these ideas not only encourage good behavior, but also have deep symbolic meaning.

In Buddhist scriptures, there are stories of humans and animals talking to each other. This symbolic language is meant to convey deeper meanings.

The idea that small actions can lead to great results is philosophically sound. Karma is based on the “principle of correspondence,” and is not based on quantity. The result of karma is almost always greater than the initial cause. As illustrated in nature, a single seed can produce many grains. Similarly, the island of Manhattan was bought from an indigenous person for only two dollars, but it is now worth billions.

The fact that the results of karma are greater than its cause is also observed in the way that cells divide. A single sperm and egg can produce a human body composed of trillions of cells. If one cell is able to create billions of cells, then it is possible that karmic results are also similarly magnified.

Therefore, it is important to look beyond the surface when reading Buddhist scriptures and examine the underlying philosophical ideas.

(2) While a cause can produce multiple effects, it cannot produce infinite effects. A sperm cell can divide into a human body, but the process stops there, and the children of that person will have their own cause and effect. One cause cannot create infinite results, or else it would contradict the principle of correspondence.

The religious implication of the finite nature of karmic effects is that the negative karma of a person does not lead to infinite suffering. Even the worst realms of hell are not permanent. Similarly, all good karma is temporary.

The concept of heaven in traditional Buddhist cosmology has various levels, and is also not permanent, except for the pure realm of the Buddha.

The Christian idea of heaven as a place or state of being is less clear. If heaven is a place of eternal life, it would be possible. Because they believe God to be infinite, then it is possible for a finite human to enter heaven through the grace of God.

Buddhism, however, adheres closely to the principle of correspondence, which states that only an infinite cause can produce an infinite effect. Limited good karma cannot lead to ultimate liberation. Only that which transcends limitations can be said to be infinite, and lead to infinite and eternal liberation. Thus, Buddhism prioritizes self-reliance, which may have a connection to the karmic principle of correspondence.

VII. Karma as a Force in Forming Character

Karma shapes our character. As the Buddhist master Gampopa said, “If someone liked to kill in a previous life, they will likely like to kill in this life. If someone liked to steal, they will likely like to steal again”. Some people are naturally drawn to killing, while others are naturally compassionate. We could say, “if a person continues to do a certain thing, they will become that thing”.

Someone who spends 30 years as a police officer will think and act like a police officer. Someone who spends 30 years as a carpenter will think and act like a carpenter.

A dentist might look at animals at the zoo, noticing their teeth. That same dentist will likely discuss teeth and their various features with others. A businessman will see numbers everywhere, and will be calculating his profit in any given situation.

It is true that our habits define us. Without habit, there could be no personality. Psychology has limitations, which makes it difficult to explain some genius-level traits in people. The gene theory has its limitations, and cannot explain the genius of figures like Mozart or Einstein.

The body does influence the mind, but physiology is not the only influence. Buddhist philosophy, with its system of rebirth and karma, has a much more holistic and logical system, as compared to some schools of psychology, which only use a limited perspective.

The concept of reincarnation is more than an old wives’ tale. It has great philosophical implications. If we accept that humans and animals have instincts, it would be logical to accept that reincarnation is real.

The formation of character is not entirely a process of predestination, however. Our genetic predisposition can be modified through effort, education, and environment.

Therefore, character is formed through a combination of innate karmic tendencies, external factors, and individual efforts. It is not a completely predetermined nor a completely malleable process, but a combination of both.

So far, we have explored the Buddhist idea of karma from six different perspectives: karma as a force, a mystery, destiny, a relationship, a moral law, and a force in the formation of character.

VIII. The Origins of Karma

The origins of karma are not clear, but it is known that it predates Buddhism. The indigenous Dravidian people of India may have had ideas about karma, yoga, and liberation. The religious tradition that most resembles this early tradition is Jainism. Early Buddhist texts describe interactions with Jains, and there are similar elements shared between early Buddhism and Jainism. There are some key differences however, which are worth discussing.

According to Buddhism, good and bad karma are based on the intention of the mind. If an action is done without intent, then it is not considered to be a karmic action.

Jainism, on the other hand, has a more mechanical view, stating that all action leads to karmic effects, regardless of the intentions of the person. For example, if a person accidentally kills an animal, then they are still said to acquire the karma of killing.

This rigid approach to karma led Jains to the idea that suffering can be completely removed through the removal of karma. This can be achieved through self-inflicted hardship to compensate for negative karmic action. If one does not create new negative karma, then it is possible to eliminate all karma.

This difference in opinion was refuted by Buddhists.

Buddhism prioritizes the intention of the mind, which is a revolutionary idea within the concept of karma. The action is not considered when assessing the karmic weight of an action. Instead, the heart and mind must also be considered, creating a moral dimension.

As the Buddhist master Buddhaghosa said, “Buddhists are like lions, who will attack those who harm them, while Jains are like dogs, who will bark at a stick instead of their aggressor”. Therefore, it is a waste of effort to engage in self-harm. The way to remove suffering is to remove the cause of suffering.

This shows us that the karmic principle of correspondence in Buddhism is not mechanical, allowing for a system of free will within the karmic system.

In short, the Buddhist concept of karma is an extremely complicated, far-reaching religious philosophy. Here is a brief summary:

(1) From a cosmological point of view, karma is a force that can create, motivate, and destroy individuals, and even the entire universe. (2) From a moral perspective, karma is a perfect moral law that ensures good actions are rewarded and bad actions are punished. (3) From a metaphysical perspective, karma follows the principle of correspondence, and is ultimately mysterious.